Table of Contents

-

Were Comfort Women Sex Slaves?

- Comfort Women Were Sex Slaves

- Which Domestic Law Did Comfort Woman Suppliers and the Police Constitute Violate?

- Is the Testimony by Former Comfort Women Credible?

- On the Criticism that the Label, “Comfort Woman,” Is Wrong

- Comfort Women Who Were Japanese Nationals after Japan Lost the War

- How Comfort Women Worked and How Much They Were Paid I: Re-Examination of the Contracts Drawn Up by the Comfort Woman Suppliers

- How Comfort Women Worked and How Much They Were Paid II: Re-Examination of the Contract Manual of the Japanese Military

- How Comfort Women Worked and How Much They Were Paid III: Criticism of Hata Ikuhiko’s Theory

- How Comfort Women Worked and How Much They Were Paid IV: Ms. Moon Ok-su’s Savings Account Book

- How Comfort Women Worked and How Much They Were Paid V: Remittance Made by Ms. Moon Ok-su and Other Matters

- Is It All Settled Now That Japan Has Paid Reparations to Korea? I

- Is It All Settled Now That Japan Has Paid Reparations to Korea? II

- On the Question: Why Do We Have to Apologize Again and Again? Give Us a Break.

- Did Comfort Stations Prevent Raping from Happening on the War Fronts?

- Closing Remarks

1.

Were Comfort Women Sex Slaves?

The title sounds like something taken from an Internet right winger site ![]()

There are still a lot of people who are fooled by the false propaganda that is rampant on the Internet. I hear that even some among those who are in the counter-movement community are fooled by it. Dr. Watanabe, an FB friend of mine, has told me about it. Luckily, many of my counter-movement friends read my pages on the Internet. So, as a review of this issue I have decided to put together, in a clear and simple way, something about the comfort women who worked for Japanese military. It is my hope that this article helps you when you review what you have learned on this issue so far, and I also hope it will serve as a tool to counter the Internet right wingers. At this point I do not know how many chapters there will be. I intend to answer any questions you may have as thoroughly as possible.

Before I begin discussing the comfort women issue, I would like to explain one strategy I use that I believe is effective in countering the right wing demagogues and their “groupies.”

Those right wingers believe in total lies and attack us with hate.

So, with the kind of details I will present in the subsequent pages, I yell at them in the street:

Dumb, stupid, ****, scum, get lost!

I am fully aware that some of you do not approve of such abusive language, but these people deserve this much abuse (I think).

It may look like two groups of idiots throwing verbal dung at each other. I yell, “Stupid, scum,” for a reason; there is logic behind it. I would hope that you at least see that I am not another one of those who spouts abusive language because he has nothing else to say. Well, not a very convincing excuse, I admit.

So why do I do it?

The ideologues among them, who can almost be called prisoners of conscience, intentionally distort history to serve their political cause. They are professional right wingers, professional demagogues. They know what they are doing and saying, so they wouldn’t budge when they are criticized and even when they are argued down. Some of those who wave the flag of Japan and shout out loud in the street are also almost prisoners of conscience in their belief in discrimination.

These action-oriented activists are also incorrigible. No matter how they are criticized they wouldn’t change their behavior. They will be demagogues and advocates of discrimination until they die. It is futile to try to take them seriously.

Nothing gets through to them. To beat them, we need to rip them from their support system. We need to separate them from their supporters and dry them up.

Logical warfare is meant to undermine the conviction that the “go-with-the crowd” segment cling on to. They are a wishy-washy bunch. I stick up my middle finger, look them in the eye, and yell at them, “Hay, Stupid!” to physically scare them away.

These two strategies look very different but designed to work together. We don’t just make noises. What we, the counter community, do is a few notches above the stupid right wingers.

This has actually gotten results. The counter action, which began in the spring of 2013, has definitely reduced the number of action-oriented conservative participants to a fraction since its heyday.

The leaders of our country see through that they cannot move forward with the mass self-protection rights and revising of the constitution in a straightforward and logical way. Democratic thinking and peace-oriented thinking are well established in Japan. They try to attack our emotion, to stir up urges to discriminate others, and other low passions, to win our heart. We just can not cave in. We need to form a coalition of peace movement, democratic movement, and anti-hatred movement.

That said, let us look at the first topic in this series. Chapter 1 will make Internet right wingers go wild because it will say that comfort women WERE sex slaves.

1. Were Comfort Women Sex Slaves?

What are “sex slaves”? Sex slaves are women who are forced to do sex labor under the condition of slavery.

What are slaves, then? A slave is a laborer who is stripped of freedom, and whose body and personhood is fettered. Having one’s body and personhood fettered means that one has been stripped of the freedom to live in a place of one’s choice, has been forced to live where the employer designates, and has no freedom to move at will. Having been stripped of freedom means that one has no choice to change jobs, resign from or terminate the employment, that one is forced to keeping working.

Some say comfort women are not slaves because, they say,

Comfort women volunteered to become comfort women.

Comfort women were paid high salaries.

Comfort women were free to go home as long as they paid back the debts.

Comfort women even had the right to deny their clients.

Let's assume these statements are true. Does it make the working condition of comfort women not of those for slaves? Let’s compare comfort women with the courtesans in the Edo Era.

In the Edo Era, prostitution was publicly authorized in places like Yoshiwara.

Prostitutes in Yoshiwara were paid certain wages, had the right to decline clients, and were allowed to terminate the employment as long as they paid back the debts.

This condition was the same as that of comfort women. Were they, then slaves or not?

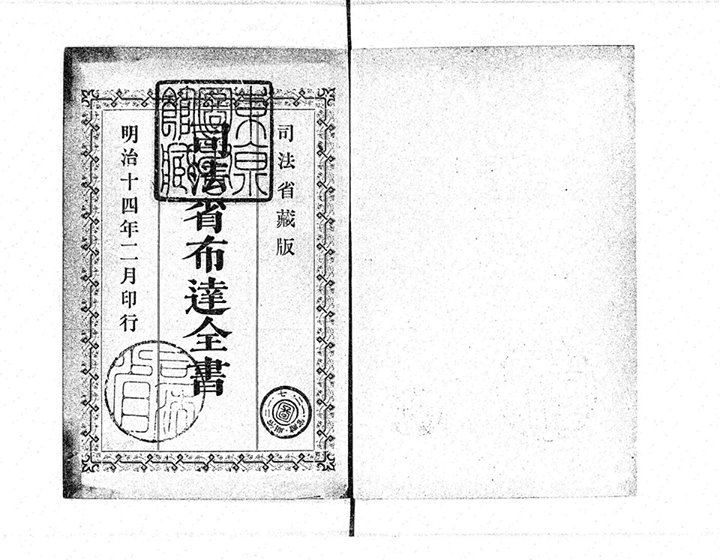

The brand new Restoration Government of Japan in the 5th year of Meiji (1873) described the courtesans in Yoshiwara as “not different from cows and horses.” This was in the official notice of the Ministry of Justice that was published along with the Emancipation Proclamation for Geisha and Prostitutes Emancipation Proclamation for Licensed Prostitutes of 1873. I will attach the document at the bottom of this chapter for your reference. In contemporary Japanese it reads, “Licensed prostitutes and geisha have lost their rights as persons, and are equal to cows and horses.”

The word “slave” was not in the vocabulary of the Japanese language at that time, but the phrase, “not different from cows and horses” suggests that they recognized slavery. So why are they “not different from cows and horses?”

No matter how poor one is, the body belongs to the person. If one loses the freedom to one’s body because of debts, the person has lost her or his last freedom, that s/he is no different from a cow or a horse. The loss of the last freedom available to a person makes her/him a slave.

If courtesans in Yoshiwara were “no different from cows and horses” because they were chained to their debts, we can say that the comfort women who were treated in a similar manner were “no different from cows and horses.”

In conventional indentured servitude, the servant is not tied down to a loan. S/he simply has a contract for a fixed term. We need to be careful not to confuse these two types of conditions.

Thus, it is not unreasonable to consider comfort women as slaves. Even in 1873 people had this much understanding of human rights. Mr. Abe and others, who live in the 21st Century, deny the notion that comfort women were in slavery. What a sad, sad situation.

In the meantime, the Japanese government had this much good sense at the beginning of the Meiji Era, but went backward in their discernment later. They started saying, “Contracting licensed prostitutes is not human trafficking, and thus, licensed prostitutes are not slaves.” In the next chapter I will discuss why this happened, and why comfort women were sex slaves after all, given this degenerate remark.

Reference

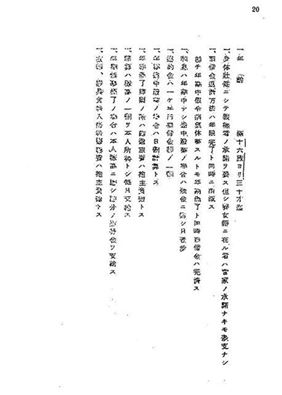

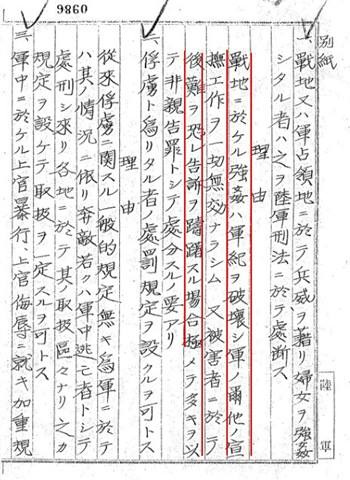

Official Notice of the Ministry of Justice, No. 22, Clause 2, October 9, 1873

![]()

“Licensed prostitutes and geisha have lost the rights to their body, and are no different from cows and horses. It is unreasonable for humans to demand payback of goods from cows and horses. Thus, monetary loans to licensed prostitutes and geisha, who are equal to cows and horses, and any outstanding credit shall not be collected.”

http://ja.wikisource.org/wiki/![]()

(Handling of the actions relating to human trafficking such as lending and borrowing in connection with licensed prostitutes and geisha)

The photo below is from the Modern Digital Library. Unfortunately, this particular document does not include Official Notice of the Ministry of Justice, No. 22.

Doro Norikazu

July 29, 2014

2.

Comfort Women Were Sex Slaves

1. Know the Difference between Legal Prostitution Contracts and Illegal Prostitution Contract

In this chapter I will discuss that comfort women were sex slaves even from the standpoint of the domestic law of Imperial Japan.

In the previous chapter we saw that the Meiji government recognized that the contracts for licensed prostitutes were slavery contracts because, they say, licensed prostitutes were “no different from cows and horses.” It was because the contract for licensed prostitutes constituted human trafficking and because the contract took away the freedom to the person’s own body.

Department of State Proclamation No. 295, 1873

“Selling and buying humans have been prohibited since olden days. However, in reality the practice goes on in the names of fix-term, indentured servitude and others. The capital (namely the contract fee which is loaned to the parents) used to hire the prostitute is considered stolen money. The plea that the money be paid back is denied.”

It seems like some would justify their act of forcing people into prostitution by saying, “I didn’t buy my daughter; I adopted her. The parent has all the rights to have his/her daughter do whatever s/he wants.”

The Department of State Proclamation goes on to say:

“Trading children and women for money and calling it adoption, making them to work as licensed prostitutes and geisha, is practically human trafficking.”

The Meiji government did not prohibit prostitution, but prohibited prostitution when it was based on human trafficking contracts. This Department of State Proclamation was repealed in 1900. The Department of State Proclamation completed its function because The Regulations Regarding Licensed Prostitutes (Department of Interior Order, N. 44) were issued in the same year.

The Regulations Regarding Licensed Prostitutes prohibited prostitution in general. However, they permitted prostitution as an exception when the practice observed certain conditions stipulated in the law. Because of this, the Imperial government maintained that, “contracts for licensed prostitution are not slavery contracts.” The law stipulated that, “no one is allowed to prevent [the prostitute] from retiring from her work.”

The Regulations Regarding Licensed Prostitutes recognized the prostitute’s “right to cancel the contract,” and “freedom to retire.” She could retire anytime as long as she submitted the application to the police. On the other hand, it was not possible for slaves to cancel their contracts.

Contracts for licensed prostitution are different in that they do not fetter the body and personhood [of the prostitute] into her identity, and thus they do not make [the prostitutes] into slaves.

Prostitutes were free to retire as long as they submit a statement [to retire or terminate the employment]. This is an important point to keep in mind.

If the prostitute had loans, the debt contract was still in effect when she left her job. In reality, some were not able to retire as long as she had the obligation to pay back the loan. It no longer took the form of human trafficking, but they (the prostitutes) were placed in the state of debt servitude.

The freedom to retire was in fact legally guaranteed. The person could retire if s/he could be bold enough to pass the debts to the co-signer (usually the parent). If the person declares bankruptcy, the person herself /himself got off the hook. It was illegal for the employer to force the prostitute to stay just because she could not pay back the debts. We find a lot of sentences like these by the equivalent to current Supreme Court.

2. Was the Comfort Woman System a Legal Prostitution System?

The act of the parent making his/her daughter a prostitute because the daughter was the collateral to the loan was called ”body-selling.” There were many instances of body-selling in poor farming villages. As the expression, “body-selling”, indicates it is practically human trafficking, but legally it was not considered human trafficking because the daughter had the freedom to retire, and thus she was not collateral.

Thus, those who deny the existence of comfort women argue that “comfort women were not the only ones who suffered atrocity, nor were they slaves. Comfort women for the Japanese Military practiced prostitution under the “body-selling” contract. It was an atrocity, but was common practice at that time. It was also legal.”

Are they right?

Let’s assume, for the time being, it is legitimate to say that body-selling contracts are not slavery, and examine what exactly comfort women contracts were like.

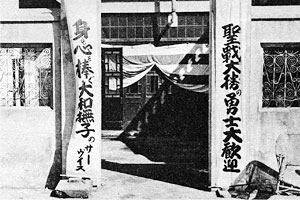

Most documents concerning comfort women are almost all lost, but luckily the original contract copies from Malay Military Administration District still exist (see photo). Malay is current Malaysia.

The Southern Expeditionary Army, which occupied Malay at the time, placed the jurisdiction authority for comfort women with the Southern Expeditionary Army headquarters, and not with the Division. Therefore we can surmise that the contract was used in South Eastern Asia as in Malay Military Administration District.

This is what this document says:

“The employer and workers are not allowed to change jobs or change affiliations without the authorization of the Military Administration.”

“When the employer and the worker want to terminate the employment, they must submit the application to the local governor and receive permission from him.”

Comfort women needed permission to retire. They were not allowed to retire without the permission from the authority. They could not retire from their jobs at their own will.

We have seen earlier that prostitutes needed to submit a statement [to retire or terminate the employment] when they wanted to retire or terminate the employment. They were free to terminate the employment as long as they submit the statement, and the Imperial government insisted that was why their employment was not human trafficking, which binds one’s person to her/his identity, that it was not the slavery contract.

Comfort women were different. Termination of the employment needed permission. There was no freedom to retire. Thus their contract that binds one’s person to her/his identity amounts to human trafficking. In other words, comfort woman contracts were slavery contracts, which the Imperial government prohibited. Moreover, it was the government office that granted permission. The government was directly involved in the maintenance of the system of biding one’s person to her/his identity=the system of slavery. The Japanese government has no business arguing, “comfort women are not sex slaves.”

Doro Norikazu

July 30, 2014

3.

Which Domestic Laws Did Comfort Woman Suppliers and the Police Violate?

In the previous chapter we saw that the Southern Expeditionary Army forced the slavery contracts upon comfort women, which the Imperial government prohibited.

Government organizations including the military and comfort women employers violated many other laws, so let us look into it in this chapter.

You will see clearly that prostitution was legal but employing comfort women was not.

- Violation of the Regulation Regarding Licensed Prostitutes

The military exercise the police authority in occupied areas because the military establishes a military administration. However, they enlisted comfort women, not in occupied areas, but mostly in Korean Peninsula and inside Japan, where the Regulations Regarding Licensed Prostitutes were enforced. Comfort women were hired on the condition that they would work overseas, but the Regulations Regarding Licensed Prostitutes did not anticipate such conditions. In Clause 7 it states, ‘Prostitutes shall not reside in areas other than that which is designated by the municipal order.’

However, where the comfort women were sent was a military secret, and thus the government agency was unable to designate their domicile. The system of comfort women itself is fundamentally illegal.

The Regulations Regarding Licensed Prostitutes stipulate the following, but comfort women were pretty much outside these regulations, and there is no evidence that the military who contracted the employers reinforced this law.

- Any one who wishes to be a licensed prostitute must describe the unavoidable circumstance which compels her to become one, and submit it to the head of the police district with signatures from both parents and two guarantors.

- The applicant herself must appear at the police district office and file the application.

- The police must interview the applicant in person to confirm the intent of the applicant herself.

- Anyone who wishes to be a licensed prostitute must submit the letter of confirmation by the head of the police district to the Metropolitan Police Department.

- Any one who has not reached the age of 18 shall not become a licensed prostitute.

None of the above were rarely observed.

As you see, comfort women contracts were illegal, because they were against the Regulations Regarding Licensed Prostitutes. The traders should have been prosecuted under normal circumstances.

- Violation of the Civil Law Clause 90 (Public Order and Standards of Decency)

(Any legal action that aims at disrupting public order and standards of decency will be nullified.)

When one conceals that a contract is illegal, and takes advantage of the other party’s ignorance of the law and has the party sign the contract, the contract will become null because it is against public order and standards of decency, according to the Meiji Civil Law, Clause 90.

Becoming null means that the contact has never existed.

- Violation of the Criminal Law Clause 226

(Abducting and kidnapping a person for the purpose of transporting the person overseas)

(If a person abducts and/or kidnaps another person for the purpose of transporting her or him overseas, the person will be sentenced to prison for 2 years or longer.)

To take someone away by deceiving her or him even though the contract is null and void constitutes abduction.

The definition of abduction, seen in legal precedents, is as follows: Removing a person from her/his living environment illegally by means of deceit and kidnapping in order to place the person under the abductor’s or a third party’s control by force.

The case of comfort women fits exactly the description of the violation of Criminal Law, Clause 226, where kidnapping for the purpose of taking the person overseas is ruled illegal.

The perpetrators, which include the employer, the Home Ministry who authorized the trip, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs who issued the ID, and the Military who assisted the transportation, are all accomplices and guilty.

To deviate from the topic for a moment, Ms. Arimoto Keiko and three others, who were victims of the abduction by North Korea, entered North Korea on their free will, having been told that they would have the opportunity to obtain good jobs.

Although their action was made on their free will, this still constitutes kidnapping because they were taken to North Korea by deceit. The government recognizes Ms. Arimoto and the others who were kidnapped as victims of abduction, so here kidnapping is considered abduction.

Abduction is synonymous with forced displacement.

Thus, comfort women, who were taken away under a false pretext that good and legal jobs would await them, were in fact kidnapped. According to the definition by the Japanese government, they were abducted, and forcefully taken away from their domicile.

- Violation of Criminal Law Clause 227

〈3. When a person transfers, receives, transports, or hides another person who has been plundered, kidnapped, or sold and bought for the purpose of making profits out of, inflicting an act of obscenity to, or inflicting physical harm or death to this other person, he or she will be sentenced to 6 months or longer and 7 years or shorter in prison.〉

Comfort women were kidnapped because someone intended to make profits out of them and to inflict an act of obscenity on them.

Operators of comfort stations handed comfort women over to the military, and the military received and transported them. Both parties are joint principal offenders of Criminal Law Clause 227.

There is no way anyone can defend these multiple violations of the law. This is a state crime where government organs, including the military, were directly involved.

- A Precedent Where The Law Was Actually Enforced

In 1937, the Supreme Court handed the guilty verdict to the trader and his associates who tried to take some women out of the country for the purpose of prostitution. Fifteen Japanese women were sent from Nagasaki to Shanghai as prostitutes by a trader and his associates. The 4th Criminal Division of the Supreme Court rejected the final appeal on the ground that “the joint principal offenders” “kidnapped women and transported them overseas.” They were guilty as charged.

When the law is properly executed, the guilty verdict is issued. The reason this trader was found guilty, though, was because he was not connected to the military.

It was a time when no one could fight against the authority of the military.

It does not make one feel good to admit that Japan was such a country in the period of Imperial Japan. However, if we are willing to learn a lesson from history, we can choose a different path. If we justify the history, similar future will await us.

![]()

http://hougakuzasikirou.nobody.jp/ron/kei/kei-ronsyou33.html

Doro Norikazu

July 31, 2014

4.

Are the Testimonies by Former Comfort Women Credible?

(This chapter is cumbersome and long.)

Testimonies by former comfort women do not ring true in many cases. That she watched TV on the ship while being transported. It cannot be true. Human memory is unreliable.

Koreans publish such unnatural testimonies without altering it. It seems they do not “coach” the woman that there was no TV during the war. They understand the basic principle of oral history data collection: record the testimony as is, even if we know it is incorrect.

Ms. Kim Bot-ton is a former comfort woman.

The right wingers have launched an all-out attack on the validity of her testimony, saying that her testimony is questionable.

Ms. Kim says she went to Singapore with the 15th Division, but it is a lie, because the 15th Division was a unit in Burma. Ms. Kim says that she was forced to be a comfort woman at the age of 14, worked for 8 years, and was released at the age of 19. The arithmetic is inconsistent. Can’t she even do additions? She is a fake comfort woman, and so on and so on. To this day, she repeats what seems to be inconsistent everywhere she gives a talk. It is as if she is saying that that is what she remembers no matter how inconsistent it is. Perhaps she has confidence in her memory based on her personal experience.

In this chapter we will examine how unreliable her testimony is.

-

Memory That Goes Against the Public Documents of the Time

Ms. Kim’s Testimony: I traveled with the Headquarters of the 15th Division of the Army to Taiwan, Guangdong, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Sumatra, Indonesia, Java, Singapore, and Bangkok.

(Testimony at the gathering: Dear Mayor Hashimoto, this is the truth about the Japanese military’s “comfort women” issue, September 23, 2012)

http://blog.livedoor.jp/woodgate1313-sakaiappeal/archives/18155831.html

Ms. Kim: First I was put into the comfort station in Guangdong, China.

( ![]() June 3, 2013)

June 3, 2013)

http://chosonsinbo.com/jp/2013/05/0527ry03/

Ms. Kim testifies that she went to various places with the 15th Division. Public documents contradict this testimony. The record of the 10th Army Hospital of the Southern Expeditionary Army, dated August 31, 1945, lists Kim Bot-ton as a military employee, and that her family registry is hers. They say there is no doubt that it is Ms. Kim.

“The record that lists the real name of the former comfort woman of the Japanese military, Kim Bot-ton, has been discovered” (an article in ![]() )

)

http://f17.aaacafe.ne.jp/~kasiwa/korea/readnp/k285.html

The name of this record is:

“Korean Personnel Away List of the 4th Section of the Southern Group of the Unit directly under the 16th Headquarters”

![]()

As the title of the record indicates, Ms. Kim Bot-ton was under the command of the 16th Army, which was stationed in the Island of Java, Indonesia. No one would have been in a place like this other than comfort women. She was no doubt a comfort woman.

It is an indisputable fact.

However, the 15th Division, which Ms. Kim Bot-ton testifies she was with, fought in Burma.

The two divisions had no connection whatsoever. Ms. Kim Bot-ton testifies she went to Singapore and Indonesia, but the 5th Division was never in these places. If Ms. Kim indeed was with the 15th Division, there are many unsolvable contradictions.

It is important to honor one’s memory, but if it contradicts the public documents of the era, we need to assume that the public documents are correct. Her memory that she was with the 15th Division has to be wrong. However, Ms. Kim’s testimony is very realistic if we ignore where she mentions the 15th Division. Let us examine how it is so.

First let us start in Guangdong.

- The Guangdong Period

Testimony #1: First I was put into the comfort station in Guangdong, China.

( ![]() June 3, 2013)

June 3, 2013)

http://chosonsinbo.com/jp/2013/05/0527ry03/

Guangdong Province adjoins Hong Kong and Macao to the north, and is famous for its Shenzhen special economic zone. Ms. Kim says she was taken there when she “was 14.”

(Testimony at the gathering: Dear Mayor Hashimoto, this is the truth about the Japanese military’s “comfort women” issue, September 23, 2012)

We saw earlier that she was 19 in August, 1945, so she was born in 1926.

She was born before the war ended, so, using the method of counting ages common at that time, she adds one year to her actual age when she counts her age. She was taken away at the age of 14 in her calculation, in 1939.

What was going on in Guangdong in 1939?

In the previous year, 1938, the Battle of Guangdong was proclaimed. The battle commenced in October. By November, all major strategic points had been occupied.

The Japanese military began occupation of Guangdong then. A three-division corps, consisting of the 5th, 18th, and 104th, was deployed.

The next year, public peace was stabilized, at least in the urban section. This generated a demand for a large number of comfort women. Ms. Kim Bot-ton was taken there right during that period. There are no discrepancies between the battles fought by the Japanese military and her testimony.

Why was she taken there at such a young age? There is a document that explains it.

At that time the Japanese military was plagued by VD, and it seems they were looking for “young women” of Korea. There is a document from a different area named, “The 14th Division Medical Corp Document,” dated April 10, 1938, and it has this description in it:

“According to the test results of Chinese prostitutes, almost all of them tested positive of DV. Thus, do not go to Chinese brothels.”

It means that local prostitutes had DV and could not be used as comfort women.

In the same time period, the document called “the 11th Army 14th Base Hospital Document” calls comfort women who were sent from Japan “tramps,” and they encouraged to use the “young women” from Korea who did not have DV when DV was rampant. It is surmised that Korean girls such as Ms. Kim were picked as desirable, upon request from the Military.

- From Guangdong to Malaysia and Singapore

Testimony #2: I accompanied the Headquarters of the 15th Division of the Army to Taiwan, Guangdong, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Sumatra, Indonesia, Java, Singapore, and Bangkok.

(Testimony at the gathering: Dear Mayor Hashimoto, this is the truth about the Japanese military’s “comfort women” issue, September 23, 2012)

http://blog.livedoor.jp/woodgate1313-sakaiappeal/archives/18155831.html

In Testimony #2, Guangdong, which was the first stop, is listed as the second.

This shows that the places are simply a list of stops that came to her mind, and not in the chronological order of the travel.

To clarify how the military that occupied Guangdong moved, we will number the places that Ms. Kim lists for convenience.

1) Taiwan, 2) Guangdong, 3) Hong Kong, 4) Malaysia, 5) Sumatra, 6) Indonesia, 7) Java, 8) Singapore, and 9) Bangkok. We need to note that 5) Sumatra and 7) Java are both locations within 6) Indonesia. That is, 6) contains 5) and 7).

Let us visit the places one at a time with this in mind.

November, 1941

The Imperial Headquarters ordered to prepare for the Southern Operations including operations in Malaysia. The Guangdong operation was totally a different operation from the Malay operation, and the participating units were totally different as well. It would be very unusual for comfort women stationed in Guangdong to move to Malay. Ms. Kim Bot-ton’s testimony is implausible at first glance.

However, there was one unit that was pulled out from Guangdong and sent to Malay.

The 18th Division stationed in Guangdong was added to the newly formed 25th Army and shifted to Malay. The only division which was shifted from Guangdong to Malay was the 18th Division. (The 15th Division that appears in her testimony did not participate in the operation.) And, the places in Ms. Kim’s testimony, one after another, appear in the 18th Division record. It is logical to think that Ms. Kim Bot-ton accompanied the 18th Division. The 18th Division moved from Guangdong via 3) Hong Kong to Hainan Island in preparation for their naval journey.

December, 1941

The Malay operation began, and the first attacks were against Thailand. Having traveled on the sea, the 18th Division was stationed in 9) Bangkok, the capital of Thailand, as a unit of the 25th Army. It took no time for the Japanese army to occupy the entire Malay Peninsula. The 25th Army began the Singapore operation, and occupied Singapore. The 18th Division was stationed in 8) Singapore.

Let us check under whose jurisdiction the comfort stations were. Records show that there was no clear definition of jurisdiction in the Chinese Front. It seems each unit managed their own. It is not good for the control of the military if lower level units get directly in touch with Japan and the Governor-General of Korea and ask for comfort women. Perhaps because of this experience, the Southern Expeditionary Army centralized the jurisdiction under the Military Government. The Military Government is not under individual Divisions. It is an organ of the 25th Army, which ranks above the divisions.

As for Ms. Kim Bot-ton who accompanied the 18th Division from China, she must have been put under the jurisdiction of the Military Government of the 25th Army as it was the rule.

- To Indonesia

April, 1942

The 18th Division, which traveled together with the 25th Army, left for Burma.

Ms. Kim Bot-ton’s comfort station was directly under the 25th Army and was separated from the 18th Division. It is presumed that the comfort station remained in Singapore.

May, 1943

The Military Headquarters of the 15th Army left Singapore and was stationed in Kota Bukittinggi in Sumatera (5). (Sumatera is a place in Indonesia (6)). Ms. Kim and her colleagues accompanied this group.

- Going Home

Testimony #3: I was moved around among various war fronts, and forced to be a comfort woman for 8 years.

(The Okinawa Times, May 20, 2013)

http://article.okinawatimes.co.jp/article/2013-05-20_49450

August, 1945

Japan loses the war.

September, 1945

A record of “Kim Bot-ton, Age 19” remains in the directory of the 10th Army Hospital in Java (7).

(“Korean Personnel Away List of the 4th Section of the Southern Group of the Unit directly under the the 16th Headquarters “)

Her age is based on the method of adding 1 to the actual age, because it is a public document. Why did Ms. Kim Bot-ton leave the jurisdiction of the 25th Army and was placed under the jurisdiction of the 16th Army? It is assumed that she was to get ready to go home.

Here is a document from another unit. According to the document prepared by the Citizens’ Affairs Department of the 2nd Army at Celebes Island (dated June 20, 1946), the Allied Forces ordered that the 2nd Army had the soldiers (the 16th Army) on Java Island under their jurisdiction and assembled them at the Port of Parepare.

The survey on the comfort station, which had been under the jurisdiction of the 16th Army, was also put together by the 2nd Army. This is irregular, given the combat ranking in the Japanese military. They say they did it by the order from the Allied Forces. The move was designed to facilitate the routes and ports of SS George Poindexter, the repatriation ship which the Allied Forces had prepared.

(The above documents are included in The Asian Women’s Fund’s Collection of Materials Relating to the Wartime Comfort Women Issue: Government of Japan Survey-1999, Vol. 3)

That was how things worked, so there is nothing peculiar about Ms. Kim Bot-ton being handed over from the 25th Army to the 16th Army.

1946-1947

Kim Bot-ton leaves Indonesia and comes home.

The first thing the Allied Forces told the Japanese military to do was to send comfort women home. “Allied Forces Instruction No. 1” instructs to “pull out the brothels and comfort women together with the Japanese military.”

(Allied Forces Instruction #1 to the Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Southern Expeditionary Army, dated September 7, 1945, in Collection of Materials Relating to the Wartime Comfort Women Issue: Government of Japan Survey-1999, Vol. 4)

It seems as if the Allied Forces were rebuking the Japanese military who was not acting promptly to return the comfort women home. Because the instruction was sent to the Supreme Commander, the homecoming of the comfort women was relatively early. Based on all the information gleaned from various documents, all the surviving comfort women should have returned home by June 1946.

If Ms. Kim Bot-ton returned home in 1946, she had been gone for 8 years since 1939.

This perfectly fits her testimony that she “was forced to be a comfort woman, moving from one war front to the next in Asia for 8 years.”

She should have been 20 years of age by the modern calculation method, and 22 years in the old way of calculation. The right wingers mix up the modern calculation method and the old calculation method and clamor that her arithmetic doesn’t jive.

It wouldn’t jive if we calculated her age their way. What a waste of time.

This concludes the research for this chapter.

If you had some knowledge of the Japanese military, the trail that Ms. Kim Bot-ton describes looks implausible. There is no way [she] would have moved between theaters of operation, nor her jurisdiction would have moved between two units, I thought first. To my surprise the research shows that it actually was backed by logical explanation.

Ms. Kim Bot-ton could have remembered wrong; the “15th Division” in her testimony could have been the “18th Division.” If this hypothesis is true, there is no discrepancies in the timeline of her trip, her age, and almost all the places perfectly fit with the facts.

The only mystery is “Taiwan.” We have nothing to back her testimony on it with.

Ms. Kim Bot-ton’s testimony perfectly fits with the timeline, but of the 9 places there is one that has no document to validate her testimony with. That’s how “unreliable” her testimony is. If she is a fake comfort woman and her story is all made up, how is it that she describes most of the places so accurately? That’s what I conclude. If some people still want to get hung up on the one place and insist that her story is all false and that she is a fake comfort woman, I can only tell them it is their prerogative.Doro Norikazu

July 31, 2014

5.

On the Criticism that the Label, "Comfort Woman," Is Wrong

The naysayers are hung up on the label, “military comfort women.“

The title of “military” is used to describe those civilian employees who are officially employed by the military. However, comfort women are civilians who were taken away by civilian prostitution traders, and whose clients were solders. Thus, it is wrong to put “military” in their title; they were “tag-alongs.” This is their rhetoric.

No one wants to admit that the national government supported the comfort woman system. Of course, their logic is flawed. There was a discussion on comfort women at the Diet 46 years ago in 1968.

The 058th Diet: Committee on Social and Labor Affairs, No. 21

April 26, 1968

http://kokkai.ndl.go.jp/SENTAKU/syugiin/058/0200/05804260200021c.html

Rep. Goto Toshio of the Japan Socialist Party asked questions regarding the application of the support law to comfort women, and a member of the government committee of the then Ministry of Welfare answered that [the government] granted comfort women a semi military civilian employee status with no pay [during the war].

If comfort women were military civilian employees, they served in the war.

Comfort women received their salary from their immediate employer, so the military naturally didn’t pay their salary. The government committee member suggested that comfort women were not official military civilian employees, but that they were part time workers who were “military recruits.” Ms. Kim Bot-ton whom we discussed in the previous chapter was one of those military recruits. In any case, comfort women were employees of the military, and the military provided them with lodgings, so calling them “military tag-alongs” is really disrespectful.

The government committee member from the then Ministry of Welfare also answered that the comfort women who lost their lives when the transport ship got sunken were eligible for support.

Any support law applies only to those who ”lost their lives while performing their official duties,” so he is acknowledging that comfort women were on the transport ship in their official capacity. Thus, they ware not mere civilians; to call them “military” civilian is correct.

This is important information, so I list the summary of this government committee member’s answer below.

- The military provided accommodations for comfort women while they were on the front.

- [The military] granted the military civilian employee without-pay status to comfort women.

- Some comfort women picked up the gun and fought, and played the role of military nurses, in the war zone.

- Those comfort women who cooperated with the military and were killed are recognized as official or semi-official civilian employees of the military, and are eligible for support by the support law.

- Those comfort women who lost their lives when the transport ship got sunken are also recognized as official or semi-official civilian employees of the military, and are eligible for support by the support law.

(Photo)

The same committee member also stated: Because of the nature of the work, some [former comfort women] may have difficulty coming forward. Some may be shedding tears without knowing about the support law. We would like to do our best to save every single one of them.

When he said “every single one,” he meant “every deceased comfort woman who cooperated with the military, who lost her life when the ship was sunk in transit, who was recognized as an official or semi-official civilian employee of the military,”

and her surviving family. No support was provided for those comfort women who survived.

How have those survivors lived the post war period?

The next chapter is on this topic.

Doro Norikazu

July 31, 2014

6.

Comfort Women Who Were Japanese Nationals after Japan Lost the War

In the previous chapter we saw that comfort women were treated as semi military civilian employees. Some were killed in the war front as combat supporters, some died in transit when the transport ship was sunken. In these cases the surviving families were eligible for the survivor’s pension.

However, surviving comfort women themselves received no support. How have their lives turned out in the post-war era?

Internet right wingers and stupid critics say:

“Japanese people are too decent to demand compensation.”

“We are not like people in South Korea where prostitutes oppose abolition of prostitution.” They must be joking.

A petition was read at the House of Representatives on November 27, 1948.

The petitioner was Ms. Matsui Ryu, Chairwoman of the Allied Unions of Hostesses of Osaka Prefecture. Hostesses, in other words, are prostitutes.

In her petition Ms. Matsui asks that the enactment of the Anti-Prostitution Law be postponed.

(The Diet Record of the 003rd Diet, Committee on Social and Labor Affairs, No. 10, November 27, 1948)

“During the war, we were told to serve the country as nurses and comfort women. Since we came back we have received no support. The husbands of some of us were killed in the war, which has drove us into poverty. Some of us who became housemaids have been raped by the employers, others were forced into having sexual relationships with their bosses at work. Men go about having their own way. What is wrong with making a living by working as prostitutes? Please do not enact the Anti-Prostitution Law until at least we have gained enough economic independence, or until men’s understanding of sex has improved.”

“Among us hostesses, there are angels in white who accompanied the soldiers in the front in Manchuria, Central China, Southern China, and various places in the South Pacific; some worked as comfort women and came home [after the war]; some lost their husbands in the war and are living with children, some are former dancers, bar hostesses, nurses, clerks, factory workers. All of us have worked in various professions.”

“Currently, all of us will not be able to make a living unless there is a better job than being a hostess… Many of us have chosen this profession because we were unable to survive, having sold off our clothes and other belongings.”

“ No matter how much one touts equality of men and women and observance of the basic human rights, the truth of the matter is that our society is not all that noble. The reality is that some of us who are housemaids are coerced into unwanted relationships with the employers, and at work bosses press us into unwanted relationships as well. In any occupation we choose, working women are victimized by tyrannical men, and women are struggling.”

“ We ask that the current law will not be enacted until economy stabilizes and hardship is lessened, until ordinary working women can support themselves with their salaries and have extra money to buy a dress and a pair of shoes, until young men and women can get married once they reach a certain age, until the husband is able to support the family, until everyone evolves and has a good idea of sanitation and sex education is a little better advanced, until every aspect of our culture reaches the world standards and is recognized as such by ourselves and by outsiders.”

I do not agree with her on everything she says, but it is not necessarily entirely their “fault” that they ended up in a situation where they had to say they wanted to continue to practice prostitution. The society was not very sympathetic to them.

On April 25, 1952, at the Committee on Judicial Affairs of the House of Councilors, Councilor Miyagi Tamayo urged that the Anti-Prostitution Law be enacted soon.

“ Just the survey of Yoshiwara, Tokyo, shows that there are more than 1,300 employees. This is truly astounding. How much longer will we allow this to continue?”

“ There are still [women] who were enlisted by the government as comfort women. These women happily and proudly continue to work as such. They still say they were invited by the government. I would like [the government] to do something about this situation as soon as possible. What is your view on it?”

“After the war, the Japanese government presumed that soldiers would need comfort stations, so they built special comfort stations, RAA, before the Allied Forces moved in. Many former comfort women during the war applied for the job.

These women continued to be prostitutes after the GHQ ordered to close the comfort stations.”

Ms. Miyagi Tamayo is asking how long will the government let these women do what they are doing.

“What kind of a world is it where prostitutes openly and proudly display their job.

It’s unforgivable that they still say the government made them do prostitution. “

Miyagi Tamayo’s husband was the Minister of Justice, and was a renown upper class celebrity. Here is what she wrote during the war.

“If we decide to have the decisive battle in the mainland, it is not to our disadvantage..., both from the geographical point of view and from the manpower point of view. If all one hundred million of us each become a crystal of loyalty, and if men and women together form a special attack corps and put up the best fight, there is no doubt our Imperial nation will win.”

“Japanese women have the virtue of dedication since our country began. When we only think of the noble cause, we will not be afraid of fire or bullets.”

(‘The Enemy Landing on Mainland and the Determination of Women’ Syufu no Tomo, (July Issue, 1945)

Such were her words [during the war]. As soon as Japan lost the war, she made a 180 degree turn, became a member of the House of Councilors, and supported “the Peace Constitution” and “the Democratic Constitution. During the war she did not give a hoot to ordinary women whose husbands were conscripted. She would preach to young wives who complained that life was difficult:

“ The household would not be wholesome unless the main goal of the family is to support themselves with the husband’s income only. I think it is inevitable that a new household does not have sufficient funds to run it.” “In the new era we must train people not to feel life is difficult.”

(‘Consultancy on War Time Life Planning for Newly Wed Wives,’ Shufu no Tomo, December Issue, 1941)

What she means by “not feeling life is difficult” is that people must learn that hardship is an ordinary state of things. She would write something like this without flinching, while she herself had the money to buy whatever she desired on the black market. No wonder she never reflected on the hardship of former comfort women.

She could not let former comfort women keep their only pride that “they also had served the country,” and could not tolerate mere prostitutes “continued to do prostitution happily and proudly.”

There was Ms. Miyagi Tamayo, on one end, and there was Ms. Matsui Ryu on the other end, who had to have the government specialist read her petition at the Diet meeting because she couldn’t even find a representative member of the Diet to introduce her to the committee.

Not that former comfort women who were Japanese nationals didn’t speak up.

They did. They lived through hard times together with solders, but were not even considered for the pension. They are never praised and spotlighted in the war history. The best they could do was to plead that they be allowed to continue to do prostitution. How miserable is that. They did their best to protest to the government who had put them into such circumstances. If only faintly, their voices of lament and anger still remain in the proceedings of the Diet Record.Doro Norikazu

August 3, 2014

7.

How Comfort Women Worked and How Much They Were Paid I: Re-Examination of the Contracts Drawn Up by the Comfort Woman Suppliers

There is this false propaganda circulated by Internet right wingers and right wing critics that comfort women were outlandishly high-salaried.

Their proof is the savings passbook of Ms. Moon Ok-su, a former comfort woman.

The original passbook of Ms. Moon Ok-su was kept in Japan. It had the balance of 26,145 yen in her military postal savings. According to Second Lieutenant Onoda*, the entry level monthly salary of a college graduate was 40 yen, and that [her savings] was equivalent to 54 years worth [of a new college graduate’s salary].

*Second Lieutenant Onoda: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiroo_Onoda

Their logic is that if one makes that much money, she cannot be a sex slave.

However, their logic is flawed. We will examine Ms. Moon’s circumstance later.

First, let us examine the general condition of the earnings of comfort women.

The surest way to find it out is to study their employment contract. What sort of contract did they sign before they left for war zones? A document called, “Terms for Contracts for Barmaids at the Comfort Women Station of The Shanghai Expeditionary Army,” exists.

The police captured a man walking around recruiting comfort women, and made him produce the contract. They arrested this man, but discovered that he had the backing by the military, so they let him go.

Let us look at the contract. It is atrocious.

(Photo)

It is a so-called “body-selling” contract which binds the person to her/his identity with the pre-loan so that the person has to work. This violated the public order and standards of decency, so in civil law it was invalid. In Meiji Era, the Supreme Court established a precedent in which such a contract was annulled. The contract was a fraud where someone took advantage of the ignorance of the public, made the invalid contract look as if it was legal, and had them sign on.

The contract reads that a 16 year old could sign on to become a prostitute. This would be totally illegal even if her parents consented. The maximum pre-loan was 500 yen. The starting monthly salary for a company employee in the urban area was 40 yen, so the pre-loan was equivalent to the person’s yearly income. It was a lot of money for a farming family.

The contract also stipulates that of the 500 yen, 20% was automatically subtracted as the handling fee. If one borrowed 500 yen, only 400yen reaches the borrower. One still has work to pay back 500 yen within 2 years. Twenty percent for 2 years means 10% at the ad-on rate, and the real annual rate was a bit higher. I must say that the rate of interest is unreasonably high for an employee loan.

A comfort woman had a two-year contract. If she retired before the term was up due to, for instance, illness, she had to pay back the pre-loan with an annual interest of 12%. On top of it, the contract stipulated that there was an additional penalty to pay 10 percent of the pre-loan [if she retired before the term was up]. This made it impossible for the woman to quit.

The truth is it did not affect the employer if the woman retired before the term was over. Later, in this chapter, we will calculate why it didn’t. The take-home for a comfort woman was 10 % of the gross sales. It is said that a solider paid 1 yen or 1 ½ yen per session. If the woman worked 12 hours a day, 30 minutes per soldier, she would have 24 soldiers. Of course she would need time to clean up and rest, so let’s say she could take 20 clients a day. It would translate into grossing 20yen to 30yen per day. If she worked 30 days, the gross would be 600 yen to 900 yen. She took 10%, so she would make 60 yen to 90 yen a month.

According to Second Lieutenant Onoda, the monthly salary of an ordinary entry-level company employee was 40 yen. An ordinary company employee made 100 yen a month. One hundred yen in current economy is equivalent to 500,000 yen. A comfort woman’s take home was 300,000 yen to 450,000 yen. That is if she worked 12 hours a day, 30 days a month, by abusing her body. Wouldn’t you think this is absurdly little?

The contract says that the employer pays for room and board, and provides medicine that is commonly available in the home medicine cabinet. All other expenses for clothes, underwear, cosmetics, everyday sundries, doctor’s fees if they are not for VD, luxury goods, liquor, and cigarettes have to come out of her own pocket. The women were, in principle, not allowed to go out, so they needed some pastime. If someone taught them how to gamble, the women could lose that much money in no time.

Some testified that some women had to take 40 clients a day. Surely, if the woman worked that much, she could probably save some money. However, except for those who were strong, the truth is that ordinary women with ordinary stamina and sexual abilities made surprisingly little money.

Now, if one woman grossed 600 yen a month, the employer would end up with 540 yen after he paid the woman. If he gave her a loan of 500 yen, he would get the money back in one month. If the woman worked for half a year, the employer would make a fortune. He wouldn’t even notice it if the woman retired before the term was over. Once he recovered the pre-loan, the only expense that he had would be the “maintenance and management” fees. The more the woman worked, the richer he got. Of the “maintenance and management” fees, the government paid for the building, and in some cases even the food. To the employer it was all profits.

The profits kept increasing, and they couldn’t stop laughing.

All they needed to do was to find women. It is no brainer to imagine that they poured money into a fierce competition to find women. It is said that they jacked up the pre-loan to a maximum of 2,000 yen at one time. In the world of geisha business, it was said that the more geisha worked, the more debts they accumulated. Thus, to professionals the contract which enabled them to pay off the debt in two years sounded like a good deal. From the employer’s point of view they could collect 2,000 yen in 4 months. This sounded like a great deal, so we wonder if money hungry traders always used the proper way to recruit women. We only need to look at what contemporary loan sharks and illegal “entertainment” operators do.

We have examined what the contract stipulated for the employer and the woman. Next, we will examine the contract the military wrote up.

Doro Norikazu

August 4, 2014

8.

How Comfort Women Worked and How Much They Were Paid II: Re-Examination of the Contract Manual of the Japanese Military

In the previous chapter we examined the contract drawn by the owners of the comfort stations.

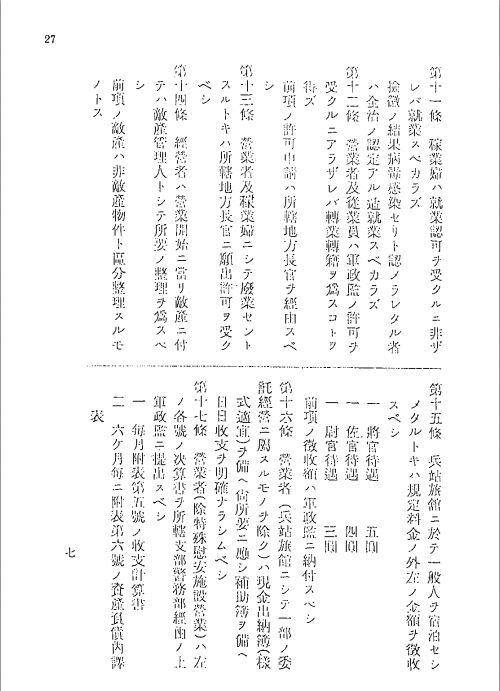

This time we will look at the regulations that were written up by the military. It describes what kind of contract has to be signed. The document is entitled: Rules to Comply Regarding the Operation of Comfort Stations and Inns in the Collection of Rules, created by Malay Military Government. In it is included Rules on Hiring Contracts with Geisha and Barmaids. (Photo)

My guess is that this had to be written up because there had been trouble between the comfort women and their employers who exploited the women with unreasonable demands.

Let us read the rules. The salary the comfort woman receives is called “the comfort woman dividend.” The rate of the dividend depends on the amount of the pre-loan.

The larger the pre-loan, the higher the risk is to the employer, thus, the lower “the comfort woman dividend.” There is no telling when the body becomes non-functional, and the employer had the right to exploit the woman more when the loan was larger. That was their logic.

- 1,500 yen or more

The employer takes no more than 60%, the woman takes 40% or more. - Less than 1,500 yen

The employer takes no more than 50%, the woman takes 50% or more. - No loan

The employer takes no more than 40%, the woman takes 60% or more.

As for the payback of the pre-loan, it stipulates that “it is 2/3 or more of the comfort woman’s dividend.” (The woman) received 40% to 60% of the gross takings, from which the 2/3 of the pre-loan payment was taken away. The so called Michener Report on Interrogation of Prisoners, which was a compilation of the inquisition of a comfort station owner who had been captured by the US military, records that the employer received 50%-60% of the gross takings depending on the amount of the pre-loan. This is consistent with the military regulation.

So far we have looked at how the women were treated from the point of view of the regulations. However, the protocol and the practice never coincide.

Let us examine another document. Here is a document that tells us what comfort women brought in.

![]()

http://www.jacar.go.jp/

[Nanning & Qinzhou Area Military Police Report, No. 445: On Comfort Stations - Memorandum], Japan Center for Asian Historical Record, Reference Cord: C13031898700

“ There are 32 comfort stations in Nanning & Qinzhou Area with 295 comfort women. The gross income per comfort woman per day averages 19 yen47cents.”

From this document it looks like the average sale was 18 yen to 19 yen. We saw earlier that we can speculate that the gross sale was 20yen to 30yen. This documents shows the low end of it. It would make the monthly gross to be 600 yen.

In the aforementioned document, Mitchener Report on Interrogation of Prisoners, it is recorded that the gross was “between 300yen and 1500yen.” If the woman was not well she may very well have made only 300yen. If the comfort woman was Japanese, she might have exclusively worked for officers and made 1,500 yen.

There could have been a wide range of situations, but I think it is not too far from the reality that Korean comfort women grossed 600yen on the average.

Suppose these women worked to death and secured a gross of 600 yen per month.

It the woman had a pre-loan of as much as 2,000yen, 60% of the gross=360 yen would be taken away, leaving her with 240yen. She then gave up 2/3 of the take home, 160 yen, as part of the payback, which left her with 80 yen.

It is equivalent to 400,000 yen in current Japan. It is about 1,100 yen per hour. It is a little better than what is written on the contract drawn by the comfort station agency, but I doubt greatly that it was appropriate compensation for the occupation of prostitution.

Ms. Moon Ok-su testifies that she bought jewelry in Burma. (This is a good example that proves it is wrong to surmise that all the stories of former comfort women are fake tragic stories.) I would say she could afford jewelry if she made 400,000 yen. However, she earned it by working as a sex worker for more than 12 hours a day and with 7,000 soldiers a year. Had one worked as excessively hard as they did, the debt would have been paid off in one year but that the body would have been wrecked. If one put someone in confinement, wouldn’t allow her to quit, made her work as a prostitute for 12 hours a day at 1,100yen per hour, and let her take one day or even a half day a month off, no matter what one may say, doesn’t it sound like the woman is treated as a slave?

In the next chapter I will finally get to Ms. Moon Ok-su’s savings book.

Doro Norikazu

August 5, 2014

9.

How Comfort Women Worked and How Much They Were Paid III: Criticism of Hata Kunihiko's Theory

I was going to write about Ms. Moon Ok-su’s savings book, but I have changed my mind and will write on a shorter topic.

On the Internet a theory that comfort women were high-salary earners of as much as 1,000yen to 2,000yen is being circulated widely. Because the salary was so high, the application rate was high as well, and there was no need to take women away forcefully. The source of this theory is none other than Professor Hata Ikuhiko a top researcher on comfort women brothels. The culprit who spread this theory to those who do not read this book was The Sankei Shinbun newspaper.

The professor has impressive credentials: former Professor at Defense University, Visiting Professor at Princeton University, and Professor at the University of Japan. It is presumptuous for someone like me to criticize a theory that is put forth by such an esteemed scholar, but I have to say a word or two.

In his book, the professor writes:

“The income distribution ratio with the employer was 40-60%, the women made 1,000yen to 2,000yen per month, and soldiers made 15yen-25yen per month.”

(Comfort Women and Sex in the Battlefields, p. 270)

This is the source from which the story spread that comfort women made twice as much as the prime minister. Let us check the arithmetic for a moment.

Suppose the woman received 50%. To earn 2,000yen, she would have had to gross 4,000yen. How many soldiers would she have had to take to make this much?

A soldier supposedly paid 1yen to 1 ½ yen per session.

To gross 4,000yen, the woman would have had to take 2,600 to 4,000 soldiers a month. If she worked 30 days, she would have taken in 86 to 130 soldiers a day!

Can anyone do it?

I hear that a soldier had 30 minutes per session. To take in 86 solders a day, the woman would have needed 43 hours a day. If she took 130 soldiers, she would have needed 65 hours a day. What an outrageous job she had. It would take 21.5 hours to 32.5 hours to gross 1,000 yen. No matter how hard she worked, there was only 24 hours a day, and a human being would die without sleep.

The Princeton professor may be good with numbers, but he doesn’t seem to have the imagination to apply numbers in real world. What is astonishing is that this theory of “high salaried comfort women” is broadcast unashamedly on TV by critics, and without even checking the arithmetic. The stupidity of it all is beyond words.

Doro Norikazu

August 6, 2014

10.

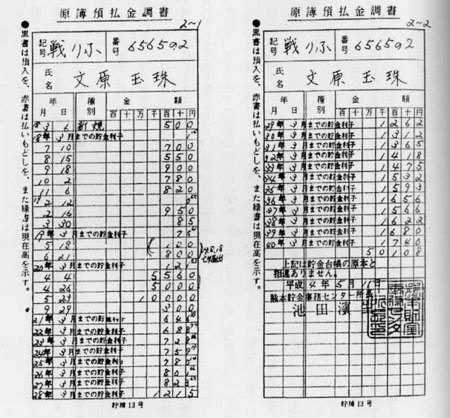

How Comfort Women Worked and How Much They Were Paid IV: Ms. Moon Ok-su's Savings Account Book (Photo)

The right wingers are spreading a false rumor that comfort women were high salaried, and that their proof is the savings account book of Ms. Moon Ok-su, a former comfort woman.

The original savings account book of Ms. Moon, a former comfort woman, exists in Japan, and it shows the balance of 26,145 yen in her military postal savings account.

According to Second Lieutenant Onoda, a new college graduate had a starting salary of 40 yen at that time, and [Ms. Moon’s savings] is equivalent to 54 years worth of salary for a starting college graduate. This leads to their argument that she cannot be called a sex slave if she was able to save that much money. Their logic is wrong.

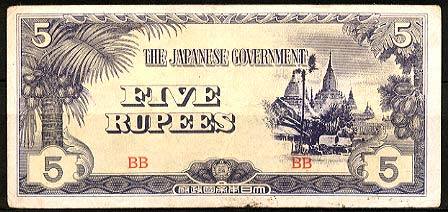

- The Truth about Military Postal Savings

First let me explain what “military postal savings” are. The word, “postal” is in the name, but is different from what we know as post office savings. Military post offices are organs of the military. The deposit was made with military scrip.

In Burma, where Ms. Moon was, the military scrip was in rupees. (Photo)

One rupee was counted as 1 yen. They were not real yen bills, however, and it was forbidden to exchange rupees into yen.

- Military Postal Savings Could not be Exchanged to Japanese Yen

The only people who were allowed to exchange military postal savings [into yen] were military personnel and civilian employees of the military, and the exchange was not made on site. They had to wire the money to Japan proper in order to exchange.

The limit allowed to wire was 100 yen per month. This amount corresponded to the living expenses. Civilians were not allowed to make the exchange. This is because the salary of the military personnel and that of the civilian employees of the military came out of the wartime budget, and thus was guaranteed by yen, but the military scrip, which the military issued in large amounts, had no backing by yen. They issued a large amount of military scrip on site and brought about inflation. The government prohibited the exchange from the military scrip into yen so that inflation would not spread to Japan.

Document #1: Managing the Economy in the South

January 20, 1942 Cabinet Decision

https://rnavi.ndl.go.jp/politics/entry/bib00374.php

Document #2: Taking Japanese Currency to the South Severely Punished by the Local Army, Osaka Mainichi Shinbun, July 16, 1942.

http://mixi.jp/view_bbs.pl?id=69155609&comm_id=5973321

The system was rigged for a self-serving reason: Japan would be unscathed even when the local community suffered from inflation. Yokohama Shokin Bank was used to handle the process.

- Ms. Moon Was Given Trash

What was one piece of military scrip worth in yen? We will get to that later, but first, let me discuss the background why she received a lot of military scrip.

She testifies that it was the “tips from the soldiers.” Let us look at the date of the entries. (See the photo of the savings book). The savings accrued between April 4, 1945 and May 23, only in less than two months, was 20,360yen.

She was in Mandalay in Burma, and Mandalay fell in March, 1945. Military scrip was not usable after that. In April, she received the military scrip that became unusable in March. Ms. Moon was given wads of military scrip that had become useless from Japanese officers and soldiers. Comfort women were not the only people who were given such military scrip. Japanese people who lived there had the same misfortune.

Those Japanese people returned to Japan and demanded that their military scrip be exchanged to yen. It was not until 1954 that these people were able to make the exchange. I hear that the maximum amount that people brought to be exchanges was 100,000yen, and mostly less.

(Questions and Answers at the Diet, 019, 1954)

http://kokkai.ndl.go.jp/SENTAKU/sangiin/019/0806/01904300806012a.html

Ms. Moon had 26,000yen, so it was pretty low on the list.

Not 1 military scrip yen was equivalent to 1 yen. The exchange rate was regulated by the law. You can check the exchange rate at the following site.

Special Measures for Handling Military Postal Savings and Other Matters(Law No. 108, 1954)

http://law.e-gov.go.jp/htmldata/S29/S29HO108.html

By doing the math using this conversion table, Ms. Moon’s savings come to 3,215 Japanese yen. The starting monthly salary for a college graduate bank employee is said to have been 5,600yen. Ms. Moon’s savings isn’t worth a month’s salary of a newbie bank employee. Ms. Moon was not rich after all.

To be continued.

Doro Norikazu

August 10, 2014

11.

How Comfort Women Worked and How Much They Were Paid V: Remittance Made by Ms. Moon Ok-su and Other Matters

In the previous chapter we saw that Ms. Moon Ok-Su was not at all high-salaried.

There is supporting evidence to her testimony. A former Japanese soldier wrote about the situation in Burma at that time. From it, it is clear that 20,000 yen or 30,000 yen was just trashed paper.

Document #1 Chronicle of Fleeing to Burma, to Moulmein (Excerpt at the end of this chapter)

http://blogs.yahoo.co.jp/siran13tb/61475733.html

In this chapter we will look into the side story to Ms. Moon’s story.

1. Ms. Moon Was Given Trash

The comfort station where Ms. Moon worked was closed after the operator ran away when Mandalay in Burma fell. Ms. Moon and colleagues ran away to Ayutthaya in Thailand together with the military, and they helped at the field hospital until they got on the repatriation ship. She saved 20,000yen during this period. Thus, the money was given to her not for her work as a comfort woman, but as tips form the injured soldiers. Soldiers didn’t mind parting with the money because they knew it was worthless. This, along with other evidence, proves that it is absolutely false that comfort women earned more than the prime minister.

2. Did Ms. Moon actually send a remittance of 5,000 yen?

Ms. Moon testifies that she sent a remittance of as much as 5,000 yen to Korea.

Forced Displacement and Comfort Women (Edited by Hirabayashi Hisae)

- After I went to Burma, I lost my savings book in the name of Fumihara Yoshiko without withdrawing the money.

- Of the 15,000 yen that I had saved up, I sent 5,000 yen from Thailand to my parents’ home in Daegu with a letter. A petty officer said I was a fool not to send all of the money to my homeland.

- I sent the money to Korea, but my brother spent it on something useless and he didn’t even buy a house.

What Ms. Moon refers to as a lost savings book shows up in the original record (See the previous picture). There is an entry called Notification of Loss 19.8.18 regarding the deposit of 900 yen on May 18 and June 21, 1944, and her testimony seems to refer to this. The original savings book was in the name of Fumihara Gyokuju, but there is another book in the name of Fumihara Yoshiko. She probably had her deposit of 900 yen in this other savings book.

As we have seen, Ms. Moon has very good memory, but there are inconsistencies as well. Ms. Moon says she withdrew 5,000 yen out of 15,000 yen in the savings book that she lost. However, what is recorded in the book is actually 900 yen.

This is probably a lapse of memory on her part.

As for the method of remittance, she must have used wartime postal service because she says she sent the money together with a letter. If she withdrew 5,000 yen and sent it, there should be a record of the withdrawal, but there is no record on that.

Could it be that she had some military scrip in addition to what was listed in the savings book? There is no way to know if what she sent via wartime mail reached Korea safely, if it was sunken on its way, or?

If it was in fact delivered safely, she sent rupee military scrip, so the people at home couldn’t have exchanged it into cash. Ms. Moon couldn’t read, so she didn’t have that kind of knowledge. She misunderstood what actually happened and is angry that she sent the money to Korea, but that her brother spent it on useless things and didn’t even buy a house. Military scrip looks just like cash, and she was given it as cash. To this day she thinks it was cash, so I think she’s better off continuing to think it was cash.

3. Would she be a rich person if we hadn't lost the war?

In theory one rupee was equivalent to one yen. Would Ms. Moon had gotten the equivalent amount of yen for the rupee she had, had we not lost the war? No, it wouldn’t have been possible.

First, there was no way to exchange Rupee military scrip with Japanese yen.

If one deposited it into the military postal savings, one could exchange it into yen.

However, the rule stipulated by the Japanese government was that exchanged yen was not to be sent to Japan proper.

Document #2: Indicator of the Construction of Great East Asian Economy, Yomiuri Shinbun, February 18, 1942. (Excerpt listed at the end of this chapter.)

Document #3: Regarding the Foreign Exchange Management in the Occupied South (Excerpt listed at the end of the chapter.)

Document #2 says sending money to Japan proper was forbidden.

Document #3 says that what was allowed to be sent was limited to “salaries that are paid by the military to the military personnel and civilian employees of the military, travel expenses, and other wages.” Comfort women’s income was not “paid by the military,” so it did not fall into the category of “military-related.”

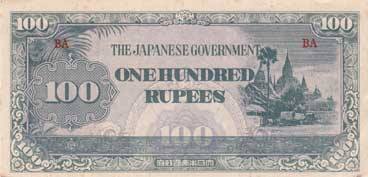

Civilians, who had to support their families back home, were allowed to send money [to Japan proper] with permission, but the amount was limited to “no more than 200 yen or equivalent per month.” The system made it impossible to send a large sum of money. Furthermore, Ms. Moon didn’t have a family to support, so she wouldn’t have gotten permission for it anyway. In addition, regardless of the outcome of the war, the value of military scrip kept falling even during the war because of the inflation. They issued 100 rupee scrip, which is equivalent to 500,000 yen. The value of military scrip was that badly devalued. (Photo)

We have so far proven that Ms. Moon’s 20,000 yen had no value.

I am going to add what happened after the war. When the wartime government ordinances became ineffective after we lost the war, the government issued the Urgent Financial Administrative Order and froze savings accounts so that people couldn’t make withdrawals. They only unfroze the accounts after they converted [the currency system] to new yen. By then the old yen, when paid back in full face value, did not amount to anything much.

We will next examine the argument that [the comfort women issue] is all done and be over with because “[we] have made reparation [to South Korea].”【Document #1 Diary of Fleeing to Burma – to Moulmein 】

“We are from the accounting department. We are going to burn the vehicles and cargo. Feel free to take anything you need,” they said. I was older than most solders and self-assertive, so they might have thought I was an officer. They continued, “There are a few officer’s uniforms. Why don’t you take a couple or three of them…?”

I answered with an air of innocence, “Thank you, but no thank you. I have my own.” They then asked, “Well, how about money? We will burn it right now, so take as much as you need. How about 200,000 yen or 300,000 yen?” “Well, I have a lot to carry, so perhaps about 30,000 yen as temporary spending money.” I took 30,000 yen’s worth of military scrip, thanked them, and went my way. In those days it would have been a feat if a company employee had saved up 30,000yen after working for a lifetime. I was really taken aback when I heard the figure, 300.000yen. It would be 300,000,000 yen in the current equivalence. I wish I had been a little more greedy.

http://blogs.yahoo.co.jp/siran13tb/61475733.html

【Document #2: "Indicator of the Construction of Great East Asian Economy,' Yomiuri Shinbun Newspaper, February 18, 1942.】

Whether it is a domestic trader or an entrepreneur stationed overseas, whenever they require temporary funds, they receive military scrip form the Southern Development Bank. Even Mitsui Combine/Family is not allowed to take the funds in yen to the local community. Conversely, if one accumulates a certain amount of funds, they are not allowed to send it to Japan proper. The profits that they have gained in the local community must be invested in local development.

http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/das/jsp/ja/ContentViewM.jsp?METAID=00841425&TYPE=IMAGE_FILE&POS=1

【Document #3: Regarding Exchange Controls in the Occupied South】

JACAR Ref.B02032868600

Go to Japan Center for Asian Historical Records:

http://www.jacar.go.jp and type in the reference number.

Clause #2

If one wants to send or take domestic Japanese currency, military scrip, or foreign currency to places other than this law is administered, one must obtain permission from the Civil Affairs Director of the district jurisdiction. The exceptions are as follows:

- When military personnel or a civilian military employee carries with him/her the salary issued by the military, travel expenses, and other wages.

- When persons other than military personnel or civilian military employees carry foreign currency military scrip which is no more than the equivalent to 200 yen for travel expenses.

Clause #5

Any person who violated any of the Clauses will be sentenced to no more than 3 years of confinement or fined for no more than 10,000 yen.

Doro Norikazu

August 10, 2014

12.

Is It All Settled Now That Japan Has Paid Reparations to South Korea? I

【Truth that is Truth Only on the Internet】

The reparations [Japan] paid to South Korea as agreed on by “Japan-South Korea Economic Agreement” includes personal compensation… This solved the issue once and for all. It is the South Korean government who spent all of 800,000,000 yen of it all on building up the economy. It is almost as if the government appropriated the money that belonged to the people of South Korea. It is the South Koran government who had concealed this fact from its people for a long time. Why does Japan have to come up with personal compensation now?

【Truth that is Truth Only on the Internet】

1. Japan has not made reparations to South Korea, nor has it handed cash to them.

You will see it right away if you read the text of the “Japan-South Korea Agreement.” Japan refused to make reparations to South Korea. What it gave to South Korea was financial aid, not reparations.

[Those who spread the false rumor on the Internet] say Japan gave South Korea 800 million dollars, but the government received 500 million dollars. The remaining 300 million dollars was a loan from the bank to the South Korean government, so whether to call it aid is a matter of opinion. They have paid back the loan portion of the “aid.”